Insights from the literature archive in Bern. Part two: under the shadow of Hesse

The doctor and psychoanalyst Josef Bernhard Lang, originally from Lucerne, was a scholar of C.G. Jung and psychoanalyst of the famous Swiss-German author Hermann Hesse. The doctor is best-known as Jungs scholar and, most important, as Hesses psychoanalyst. In this article, I aim to present Lang as an individual and complex personality of his time. Without claim of completion, in the following I will analyze extracts of a diary of Hesse (1920) and letters of Maria Moltzer (1922), Hesse and Lang (1923) and Hesse (1935).

Hesse wouldn’t be Hesse without psychoanalysis. From 1916 to 1944 the written correspondences between the writer and his doctor and psychoanalyst Josef Bernhard Lang are documented (NZZ, 15th June 2006: “Die dunkle und wilde Seite der Seele”/ “The Dark and Wild Side of the Soul”). But becoming older, Hesses view on psychoanalysis gets more and more distant. In April 1935, 68 year old Hesse writes:

“In the following discussion [with Chr. Schrempf, protestant Theologian and Philosopher] I plead for the pathological human being, and said, that hysteria would not be just an illness, but often times a salvation as well, it would help many to bear the otherwhise so unbearable life, nonetheless.”

Hesse further writes:

“His [Schrempfs] not taking seriously of art shows up (…) during discussion, he less sees in art a language, but more a way of escape and illusion, a form of bending out from the terrible.”

In contradiciton, Hesse views art as an independent way of self-expression. The root of the expression, e.g. illness, escape and illusion, only is a minor point for the artist. Hesse wants to transmit the message of his literatury work, and not an analysis of his psyche, which finally would distract from his work. And: why medicate an illness like “hysteria”, when it makes life more bearable, and, if possble, even helps to be productive? Hesse himself was constantly physically ill and in health resorts all the time, e.g. in June 1923 in Baden, canton Aargau, Switzerland. Did this hinder him from writing? And: should the reader read his texts in light of his illnesses? It is exactly what the author tries to prevent. Postmodern theories of literature science therefore speak of “the death of the author”, to honor the text as an indipendent counterpart.

Art is an independent way of self-expression

Nevertheless, Hesses life remains influenced by psychonalasis. In a diary from 1920, he writes, that he was “inspired by Freud and Jung”:

“We should, at least for once, leave all moral judgments out and look at ourselves, the way we are, or, as the expressions of the unconscious show to us, without morale, without gallantry, without all the noble glance, in our bare drives and desires, our fears and complaints. And only from here on, from this point of origin on, we then should try again to mount tables of value for the practical life.”

Hesse acknowledges the value of a proper self-introspection for the sake of one’s own authentical way of life. Striking: Indeed the writer of the diary mentions Freud and Jung, but without a single word his friend Josef Bernhard Lang.

Could be, that Lang only then gets important for Hesse, when the writer finds himself in the midst of the divorce from his first wife Mia Hesse (in full, Maria Hesse-Bernoulli, fotografer from Basler). On the 8th of March 1923 Hesse writes to his friend and doctor:

“Dear friend Lang

(…) I’m working again on my divorce, now thinking to agree with my wife and to undertake the thing, and therefore need a few lines from you. (…) It’s mostly about the confirmation that there were marital difficulties and that my friends are aware of the fact that for almost four years I’ve been living separated from my wife.”

To Lang however Hesses charm, like the one of his teacher Jung, stays unbowed. Whereas he’s jealous of Jung’s psychoanalytical genius, he envies Hesse as an artist and bon vivant.

On the 12th of March 1923, Lang writes to Hesse. He’s fully enthusiastic about the courtesan Kamala, who introduces the literary Siddharta in Hesses novel Siddharta to eroticism. Lang therefore asks Hesse, if Kamala would have a “carnal doppelganger”. And further: “I’ve never read a book that so much pleased me.” For the cure of his too high blood pressure he preferably would prescribe himself “a real Kamalacure”. He complains: “Besides, I’m getting alarmingly fat.” Obviously, Langs self-ascribed “orgiastic side” is neglected. It has been half a year since he has been partying. Only a few contact with like-minded. Alone and comfort eating, the doctor works like a beast (“travailler comme une bête!”). Rays of hope: The upcoming visitation of two astrologers, who are on their journey through to Turkey. And: Lang has started painting again, something he hadn’t donce since November 1922. He also asks about Hesses new lover and wife to be Ruth Wenger. Lang had had known the Basler concert singer and painter in Montagnola, Ticino, where Hesse had been escaped since 1919. Flattered by both gentlemen, the young women falls for the 20 year older Hesse. Lang is still hurt and can’t let go of the past. In his letters to Hesse, he constantly asks about Ruth. He learns from Hesse, that her father is ill and and hopes, that she’s not too much tormented by it. Because: “(…) I’m just too sentimental.”

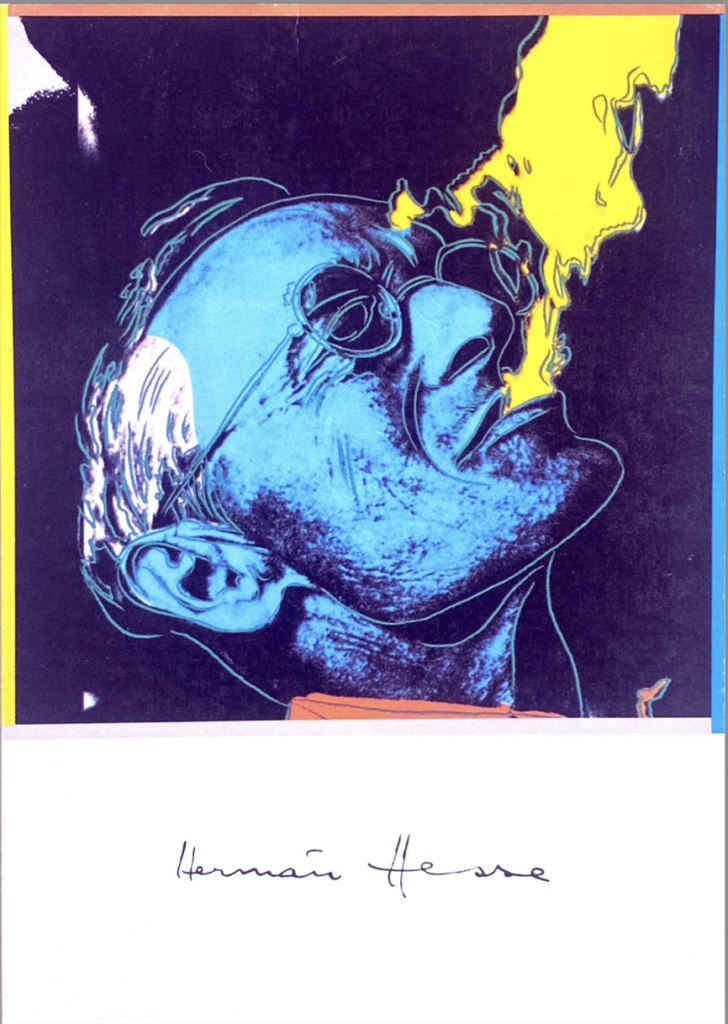

Playboy of literature. Andy Warhol might have known that, when in 1983, he made the writer into an “icon of popculture”. Hermann Hesse was married three times. Always with intelligent women: for 19 years with the fotografer from Basel, Maria Hesse-Bernoulli. The second marriage with the 20 years younger concert singer and painter from Basel, Ruth Wenger lasted for three years. The third marriage with the 18 years younger art historian Ninon Dolbin, born in Czernowitz, present-day West-Ucraine, lasted from 1931 unto Hessess death in 1962.

Too sentimental, not much of a player? On the 24th June 1923 doctor Lang writes to Hesse, that he wishes to have “more female acquiantances“. In the last years he had lived an ascetic lifestyle, he writes, because of the “fiasco with Ruth”. He thanks Hesse “for his good teachings in communicating with women” and calls him a “knowledgeable teacher in those things”.

In ihrem Brief vom 11. Mai 1922 hat seine gute Freundin und Psychoanalytiker Maria Moltzer das Problem Langs erfasst:

“Man muss den Glauben und die Liebe zu seinen eigenen Werten sich noch erwerben und ich finde immer, dass Du das zu wenig tust. Ich bin überzeugt, Du wärest glücklicher, wenn Du so weit kommen würdest, denn dann hast Du die eigne Welt immer mit Dir und bist weniger abhängig von Andren. Ich habe Dir schon einmal gesagt, dass ich den Eindruck habe, Du gäbest mir und meiner Arbeit eine Liebe, die eigentlich Dir selber und Deiner Arbeit zukäme.”

Während Lang auf die anderen schaut, auf Jung, Hesse und Moltzer, sowie Ruth nachtrauert, verliert er sich selbst.

Mangelnder Mut mag es gewesen sein, der ihn nicht zu mehr Erfolg geführt hat. Das Gefühl, in der “Irrenanstalt”, in der Privatklinik in Meiringen, interniert zu sein, wie er Hesse weiter am 24. Juni 1923 schreibt.

Lang ist eine Mischung aus Schmetterling mit gebrochenen Flügeln und Praliné mit flüssigem Kern. Am 12. Juni 1923 schreibt er an Moltzer:

“Etwas eigenartig berührte es mich, als Du zweimal von ,meiner Güte’ schriebst. Und das deswegen, weil man mir bei [Dr.] Bircher diese Eigenschaft immer vorgehalten und als Schwäche angekreidet hat. Und dann stand daneben auch Unmännlichkeit. Ich bin lange immer böse geworden, wenn man mir von meiner Güte sprach.»

Offensichtlich keine erfolgsversprechende Kombination.

Es gibt einen Wikipedia-Eintrag über:

Christoph Schrempf. C. G. Jung. Hermann Hesse. Maria Hesse-Bernoulli. Maria Moltzer. Ruth Wenger.

The translated passages are to be found in the literature archive in Bern (SLA). The article written in German from the NZZ can be requested at kontakt@valeriasogne.ch